SOVIET AND AMERICAN CREWS WORK TOGETHER TO SAVE A LIFE

from AIRMAN Magazine-September 1974

by MSgt. JERRY SMITH

"They're coming for you tomorrow, Jim. I want to make,certain that you want to go It's your life. You won't have any margins if anything should go wrong up there "

Dr Bill Knaus spoke quietly to James Torrance, who lay in a hospital bed in Irkutsk, Siberia, his abdomen swathed with bandages. Both Americans were part of a U.S. outdoor recreation exhibit touring the Soviet Union Eight days earlier Soviet doctors had operated on Torrence and stopped massive internal bleeding caused by a ruptured esophagus, but he was not recovering

Haggard, unshaven, Torrence managed a smile. "We aren't doing any good here. Let's go."

Later that night while returning to his hotel, Doctor Knaus worried about the fact that Torrence, a U.S. Forestry Service employee, was not responding to massive blood transfusions. He couldn't figure out why.

As he approached the dark hotel, the George Washington University Hospital internist ran his fingers through his curly brown hair and sighed, still concerned about tomorrow, October 24, 1973, when a U.S. Air Force C-141 would arrive in Irkutsk to move Torrence to an American hospital. If anything went wrong then he might be delivering a corpse to Japan instead of an emaciated but gutsy Jim Torrence. About the only thing Doctor Knaus knew for certain at this point was that his glasses would fog up when he entered the heated hotel from the sub-zero Siberian night.

"Air evac 629, this is Copenhagen control. It's time to contact Riga control. Radio contact is 127S.5. Over." .

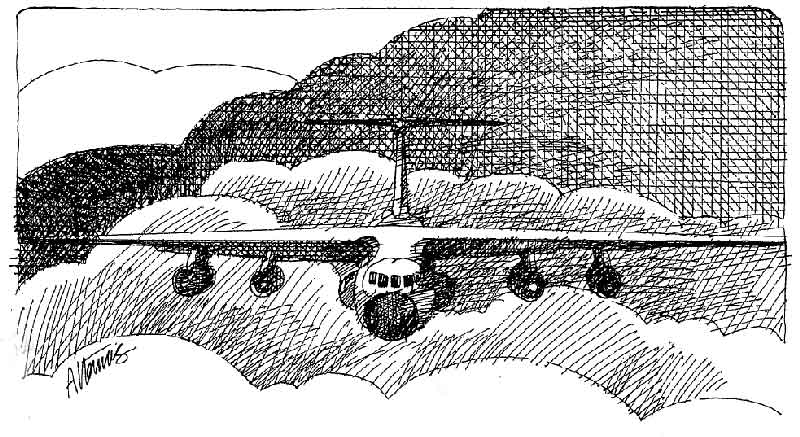

"Roger on that, Copenhagen," said Capt. "Skip" Rawlings, an Air Force reservist. He tuned in the required radio frequency. In the pilot's seat, Maj. Donald Eggerman, also a reservist, kept the aircraft on its northeasterly course. The MAC C-141 Starlifter was 36,000 feet over Latvia, the Baltic Sea far behind.

When he had the correct frequency, Rawlings pressed his microphone-button. "Riga control. This is air evac 629. We are maintaining 11,000 meters. Estimating entry point Juliet at 30." Riga acknowledged and told Rawlings to report at the entry point.

Rawlings, the aircraft commander, relaxed his 6-foot, 155-pound body as best he could in the seat harness and considered the situation. It was difficult for him to believe that in 30 minutes they would be. in the USSR. Yesterday, October 22, he and his Air Force Reserve crew were resting at Rhein Main AB, Germany, when they were suddenly notified that they might be going to the Soviet Union. By four the next afternoon, (Sunday, the day they were to have returned to McGuire AFB), they broke contact with Rhein Main's rain-slick runway and headed for the USSR. All military markings on the C-141 had been hastily painted over.

As they approached the Russian border, Captain Rawlings, who in civilian life is a flight engineer with Eastern Airlines, began to feel the enormity of the mission. Guidance at Rhein Main had been rudimentary. It amounted to this: an American is dying in Siberia, get him to Japan. Rawlings was unfamiliar with the route and the aeronautical references he had were thermofaxed copies of outdated commercial Jeppeson charts. As far as the crew knew, this was the first unescorted military plane to enter Russia in recent times. The Presidential flights of a year earlier had been escorted from Scandinavia by Soviet aircraft.

Well, flying challenging missions was the reason he had joined the Air Force Reserve last year after his active duty obligation had been met. It would take years of flying before Eastern would move him into the second seat. But in the Reserve structure he was a qualified aircraft commander.

Lt. Jimnmie Jackson, a part-time navigator and full-time physics student, interrupted his thoughts to tell him that it was time again to contact Riga.

"Riga, this is air evac 629. We're over the entry point at 31. Estimating Moscow terminal at 45."

Jim Torrence realized that he was in deep trouble. He didn't have the number of blood cells needed to carry enough oxygen to his brain. He couldn't even sit up in bed without passing out. A hematocrit reading (percentage of red blood cells) of 45 was normal for a man his age, 41. His was 13.

As a result of the exploratory operation in which the Soviet doctors had found and repaired the hemorrhaging esophagus he had an 11-inch incision down the center of his body, his system refused to replace the lost blood, and already he had been given 51/2 pints of blood. Doctor Knaus recommended evacuation to an American hospital.

The Soviet cooperation had pleased everyone connected with the exhibit. Irkutsk's mayor, Mr. N. F. Zalatsky, gave the Americans access to his Moscow hotline. An all-night stint on the telephone started the wheels that would not stop until Torrence was safely returned to his Arlington, Va., home. The mayor opened the doors to the Irkutsk University Hospital. Gregory A. Kuzemenko, Chamber of Commerce and |fjl Industry of the USSR, provided the vital link to the Minister of Foreign Affairs for Soviet clearance of the mercy flight.

Using the mayor's car, Joseph Novak, technical supervisor of the exhibit, measured the Irkutsk runway, and saw to it that there was enough proper fuel available to service the American C-141.

All agreed the unprecedented good will by the Soviets was even more significant in view of the growing Middle-East tension.

It would be a tricky landing. Everyone in the cockpit was busy converting Soviet metric descent altitude readings into feet to match the Starlifter's instruments. Cross winds on approach would be especially bothersome since the Russian readings of meters per hour had to be converted into miles per hour.

Major Eggerman adjusted the controls slightly as a cross wind nudged the Starlifter slightly right of the Moscow International runway. He peered through the swirling snow and grunted his satisfaction when the aircraft made perfect contact with the snow packed runway. He reversed the four jet engines and was relieved when the C-141 slowed down without skidding.

As he turned off the runway behind the follow-me truck, Eggerman slammed on the brakes. In the glare of the landing lights he saw something partially buried by falling snow at the entrance to the taxiway.

"lt looks like drag chutes," he told Rawlings. "Don't want to take a chance on.. sucking one of them into an engine. But how do we tell that truck to come back and pick them up?"

They waited several minutes while trying to make the tower operators understand why they were stopped on the runway. Eventually the truck returned.

Captain Rawlings freed the emergency signal light from the bulkhead at his side and flashed its powerful beam back and forth across the drag chutes. The Soviet ground crew got the idea. They hooked the chutes to the tailgate of the truck and sped off.

In the Moscow terminal Captain Rawlings and Lieutenant Jackson were met by Capt. George Kolt, assistant air attache, and an English speaking Aeroflot navigator. Both men would accompany air evac 629 on its eastern odyssey. As the Aeroflot navigator led them to the Air Ministry building to make out the flight plan, Rawlings wondered what reaction he was arousing being dressed only in bell bottom slacks, a sweater, and a blue blazer while the thermometer registered minus 18 degrees Fahrenheit outside. Jenkins was even less warmly dressed. That the aircrewmen wear civilian clothing was a stipulation that had caught the Americans unprepared. Their civilian clothing had been selected only for the fall weather in Germany.

Outside the terminal, flight engineer TSgt. Charles D. Warden shivered in the sub-zero night as he supervised a Soviet ground crew pumping 50 tons of fuel into the C-141. He made a mental note to tell his wife that if had been a woman who had wrestled the heavy, cold-stiffened hose into the refueling port.

On the flight deck, TSgt. Raymond E. Parry calculated the throttle settings needed to produce the maximum engine performance on takeoff without overboosting them. Moscow would be an awkward place to blow an engine. It would be disastrous in Siberia.

At 10 p.m. local time air evac 629 was airborne again heading where no American military aircraft had ever gone-the heart of Southern Siberia.

Two hours out of Moscow, Sergeant Warden paused at the aft end of the navigation table and listened as the Soviet navigator talked to his countrymen who were guiding the Americans across the vastness of the Soviet Union. From Moscow to Irkutsk it is 2,700 miles. From Irkutsk to the eastern border of the country it is a little less than half that far.

Next to the Aeroflot navigator sat Lt. Scott Jenkins watching the navigation .radar. Jenkins, Warden, and Parry were the only active duty members on the flight crew. Assigned to the 18th Military Airlift Squadron, McGuire AFB, N.J., they, too, had been on crew-rest when picked for the mission. Warden and Parry got the trip because the two Reserve flight engineers of Captain Rawlings' original crew encountered passport problems.

Major.Eggerman left his seat to pour his fourth cup of water. The sandy haired Air Reserve technician would drink at least a quart on this six-hour leg into Irkutsk. At these high altitudes, humidity in the constantly recycled air of the Starlifter was near zero.

As he moved toward his seat Eggerman saw a red light flash on the flight engineer's panel. Warden saw it at the same instant and immediately punched a button on the panel.

"What's the problem?" Eggerman asked, moving quickly to Warden's side.

"Filter bypass light," replied Warden. "Hope it's only ice in the fuel. I'm putting heat in there now."

To the relief of both men, the light flickered and then went out. Captain Rawlings, now in the pilot's seat, was not aware of the fuel icing which occurred several more times. Nor would he be told of it until later. Only if the light hadn't gone out would Warden have felt it necessary to tell Rawlings.

At his radio SSgt. Stephen' Long listened intently to the faint voice coming from 6,000 miles away at Andrews AFB, Md.- "How do you read me, MAC flight 640629?"

"Five-by-five."

Military Airlift Command keeps in voice contact with all of its worldwide flights. Long had taken on the responsibility of communicating with MAC so that the copilot, who usually did it, could keep up with the command controls that the Soviet navigator was reporting more frequently as they neared Irkutsk.

Long checked the foot-long list of radio frequencies that would put him in contact with other American voices if he lost Andrews. Pausing, he wondered what his boss in Philadelphia would say when he called from Japan to tell him he would be a couple of days late getting back to the college bookstore he managed. Long chuckled, looked up from the list and saw the tip of the sun cresting the horizon. Time really moves when you're flying east, he thought.

Captain Rawlings' spirits weren't rising nearly as fast as the sun he was flying into. In fact they were dropping. Below was solid cloud cover, and it was his uncomfortable task to make the final decision about going into Irkutsk.

He didn't like the circumstances. The approach charts he had were large on scale but skimpy on terrain details. He and the Soviets had gone over the charts in Moscow to update them, but still, the navigation instructions they contained were for a radio beacon approach-not the most accurate for the kind of flying he would have to do if the weather didn't break. Once it was handed off to approach control, AIREVAC 629 would come in almost blind.

"Captain, traffic control advises us that an airliner will pass beneath us to our right soon," the calm efficient voice of the Soviet navigator informed him over the intercom.

"Thank you," replied Rawlings.

He looked down and saw the dot moving bright against the clouds. That was the third plane they'd been notified about and each time the information had been precise.

He heard the navigator giving the current enroute station their altitude, heading, and expected time of arrival at the next station. This flight would be almost impossible,without him, Rawlings knew. As they droned eastward, Rawlings reflected that the reason his crew had been picked was that it consisted of three qualified aircraft commanders. Major Eggerman, of the 702 Military Airlift Squadron (Associate), had been giving Rawlings his requalification check.

Capt. Thomas E. Hurd, Rawlings, and Lt. Jimmie Jackson were from the 732 MAS (Associate). The two loadmasters were from Eggerman's outfit, and the three active duty members of the flight crew were also from McGuire. They all belonged to the 514 ^»» MAW. In the associate program, the Air Force owns the aircraft, but reservists fly the global missions of MAC. The aircraft can be manned either by all-Reserve crews or mixed crews, like Rawlings'.

"Captain, maintain your present heading and descend to 9,000 meters," the Soviet navigator told Rawlings.

Here we go, thought Rawlings. They were starting their descent at 130 miles out and it wouldn't be long before they would sink into the clouds.

Beside him Captain Hurd watched the radar altimeter closely as Major Eggerman and Lieutenant Jackson flipped through their conversion charts to give Rawlings the altitude readings in feet. This 2,-000-meter drop was gradual and there was plenty of time to make the conversions. At the lower altitudes, when they descended in smaller increments with less time to convert between readings, it would get hairy.

Rawlings had decided to go down to 1,000 feet. If he couldn't line up the aircraft direction finder with the radio beacon at that altitude, he would pull out. If the ADF needle did line up at 1,000 feet, he would take the plane lower in hopes of breaking through the clouds. To land, he would have to see the runway.

As they started into the clouds, Rawlings used every man and piece of equipment available. Lieutenant Jackson, while monitoring the approach, also kept a sharp watch for terrain features on the weather radar. In addition to his regular approach duties, Captain Hurd watched the altitude radar from the copilot's seat, and advised Rawlings when the altitude decreased below 500 feet indicated. Thus, the aircraft commander had one electronic eye looking to the front and one looking down through the clouds.

Directions were coming at him fast and steady now. He was glad that the Starlifter was a forgiving bird. He could depend on the four big Pratt-Whitney engines to give him the power to get him out of a bind. And the hydraulic controls were as responsive as power steering on an automobile.

As they descended, they had to remember that the Russian altitude information was based on the height of the altimeter at the airport-not the altitude of the aircraft above ground. Also the Soviet altimeters were set at zero. The Americans set theirs at the sea level of the airport. It was taking them two minutes to make the conversions and to move the aircraft down to the altitudes the approach wanted. It seemed to Rawlings that no sooner had they licked one conversion than another change in direction and altitude would be required.

Some of the tension left him when the ADF needle reacted to the radio beacon and he was able to line the C-141 up with the still invisible runway. As Captain Hurd advised him they were at 600 feet, the ground appeared through an opening in the clouds. Suddenly they were out of the heavy stuff, and far ahead through the haze and a heavy smog, Rawlings saw the runway lights.

From the air Irkutsk looked like what he thought an early American frontier town would be, low storied frame buildings and dirt streets.

He set the airlifter down smoothly and ran all the way to the end of the strip. He stopped, then began the 2 1/2-mile taxi to the parking ramp over a narrow and extremely rough taxiway.

Sergeant Long opened the rear doors of the aircraft so that the med techs could put a litter in the ambulance which would bring Torrence from the hospital. Crowds of smiling faces pressed in close to peer into the cargo hold. Noticing that many hats were being blown away by the 30-foot blast from the auxiliary power unit-a small jet engine in the left wheel pod-Long plugged his headset to a 50-foot extension and went outside to keep the curious visitors away from the exhaust.

In the milling crowds, Sergeant Warden lost Captain Kolt. As he looked around he spotted a woman who earlier had spoken to him in halting English. He motioned her to his side and communicated his needs to the refuelers through her. The woman told i the refuelers that Warden needed 130,000 pounds of fuel.

Captain Kolt was with Long, showing the fleet service trucks the safest way to negotiate the low wings of the Starlifter. The English speaking airport manager came out to make certain that everything was going smoothly. Long understood him to say that this was the first American plane to land at Irkutsk in many a year; a Ford tri-motor from another era having been the only other one. Long saw a sign in English over the front of the terminal that read, "Proletariat working for the good of mankind."

After TSgt. Ralph E. Noland, a med tech from the 18th AES, put the litter in the ambulance, he was caught up in the festive and curious crowd. A pretty blonde girl acted as his translator when the local people plied him with questions about the aircraft. Surprisingly enough, none of them commented on the Starlifter's bedraggled appearance. The hastily applied, insignia-covering paint had streaked badly during the flight.

After the refueling, Warden wanted to enter the terminal on the chance that he could buy a doll for his daughter. Rawlings, however, had told everyone not to stray any farther than the wing tips of the airplane. When he saw the car returning Rawlings and Jackson to the plane, Warden rushed over to tell the AC that the right brake was heating up and to avoid using it.

Minutes before the ambulance returned, the border guards returned the passports. One of them pointed to Long's passport and ran his finger back and forth to indicate that there was no mustache on the photo. Long understood. He had grown a mustache after the passport, had been made. Seeing the worried expression on Long's face, the guard laughed and handed him his passport.

A few minutes before one o'clock the ambulance returned, making its way through the crowd to the rear of the aircraft where Torrence was quickly carried aboard. Glucose and water, being fed intravenously to him, came from a bottle held high by an attendant.

Torrence looked near death. Even so, Capt. Barbara Roe, a flight nurse from the 18th AES, had to tell him to stop grinning or she wouldn't be able to put the oxygen mask on him. As soon as the doors were closed, the engines were started.

Col. Homer I. Woosley and Maj. Richard J. Woltersom, USAF physicians assigned to Ramstein and Rhein Main respectively, quickly conferred with Doctor Knaus. It was agreed that the most important consideration at the moment was getting airborne as quickly as possible to start transfusions of O-positive blood, the universal donor.

Airevac 629 began to move. Doctor Woosley noted Torrence's oxygen carrying capacity was so limited that even a slight increase in altitude might kill him, even though they were giving him 100 percent humidified oxygen. He knew that in Vietnam it had been extremely risky to move a patient by air if his hematocrit was less than 35. Torrence's was only about a third that high.

Earlier he had recommended that the cabin pressure be maintained at the lowest possible altitude equivalent, realizing it would have to climb as the aircraft climbed. A differential of only 8.6 pounds per square inch between the pressure inside the cabin and the atmosphere outside could be tolerated by the C-141. It was like blowing air into a balloon that is designed to take only a certain amount of pressure. At the moment the most important thing was getting blood started and moving Torrence as quickly as possible to a hospital. The aircraft's best operating altitude was at 39,000 with a cabin pressure equivalent to 8,000 feet. It would have to do. Torrence tried to calm himself as the Starlifter lurched and rocked down the long, uneven taxiway. He felt that he was being torn apart and when the huge aircraft finally lifted off the ground he fought the chest-constricting gravity by breathing deeply of the sweet oxygen.

When the plane leveled off and the pressure lifted from his chest, the doctors and nurses gathered around him.

Sergeant Noland and SSgt. Robert Tokarski stood ' on the outer fringe of the nurses and doctors, and as a request was called out the med techs would find the required piece of equipment neatly arranged in a large plastic box which they had fastened to a litter next to Torrence.

"Let me see a number twelve butterfly. Okay, that's not right. Give me a fifteen butterfly. Mr. Torrence keep your arm down."

When the blood was on its way Sergeant Noland made a hot cup of bouillon. Capt. Jeanie Martin, a Reserve flight nurse from the 31st Aeromedical Evacuation Squadron at Charleston AFB, helped Torrence drink it by cradling his head in her arms. The bouillon tasted great to Torrence who hadn't had anything but hot tea since the operation.

"Okay. That's enough for now," Captain Martin told him when he had finished the cup. "It's time for some sleep."

Torrence slept on and off during the next four hours.

Each time he awakened he was given bouillon and other liquids to fight dehydration. The nurses would lift him up and rub his back.

His improvement was dramatic during the 41/2-hour flight into Khabarovsk. On the ground, the nurses asked him to sit up to get him off his back.

Torrence was apprehensive about doing this. Each time he had tried it in Siberia, he had passed out.

"But you've had the blood. Your color has improved. You're more alert and your breathing is regular. Look, we'll keep the oxygen ready," Captain Roe told' him.

Torrence did as they asked and tolerated the sitting up so well that Captain Martin asked him to dangle his legs over the side of the litter. After he sat that way for several minutes he realized that he was going to be all right and started to- relax. Soon he was recounting his Siberian adventures to the nurses.

Ground time at Khabarovsk was brief but not uneventful. Doctor Woosley politely turned away five women who came out to offer assistance.

Long was having his usual communication problems. When Captain Kolt mistakenly told a curious visitor that Long was an engineer, the man made the motions and sounds of a train, then jerked his hand to demonstrate a railroad engineer pulling the whistle cord and said "Toot. Toot."

As Sergeant Noland handed over the medical personnel's passports, one of the border guards asked Captain Kolt if Noland had any Coca Cola.

Noland offered them chilled root beer in small paper cups. Only two of the men would take the offered beverage. One drank his and then drank his companion's when that man refused to empty it Noland then had to undergo a mild interrogation as to what the ingredients were.

As the navigator prepared to leave the aircraft, Colonel Woosley pinned his silver flight surgeon's wings on the Soviet's green Aeroflot uniform as a token of appreciation for his part in the flight.

As air evac 629 awaited clearance from the tower for take off, the absence of the Aeroflot navigator was apparent, for there was a communications breakdown. After a 10-minute delay, they were rolling down the runway on the final leg of their mission of mercy.

As the Starlifter's wheels thumped into their wells, Sergeant Long stood at the rear exit door and watched the large statue of Lenin, bathed in red light at the entrance to the terminal, slowly disappear into the Siberian night beneath him.

It was a powerful reminder of the vast ideological differences between these two countries that had been briefly overcome in the common denominator of saving a man's life.

Note: This article was scanned through an OCR recognition program using a pretty marginal photocopy. If there are typos it's a result of the subsequent spell check not picking them up and me missing them visually. If you find typos and want to take the time to contact me via email to tell me about them please do so. The PDF (about 1.5mb) of the original copy can be viewed here.

Last Updated: Wednesday, January 17, 2007