A Sort of Homecoming

by Tech. Sgt. George Hayward

photos by Staff Sgt. Steve Thurow

This article originally appeared in AIRMAN magazine

The C-141 was on static display at Randolph Air Force Base, Texas, for a one-day stop during an eight-day airlift mission that would take it across the Pacific Ocean. Tech. Sgt. Henry Harlow and other crew members chatted with visitors in the aircraft’s open cargo bay, explaining its prominence in the Vietnam War. A thin, 50-ish man stepped forward with a question.

His name was John Blevins. A retired lieutenant colonel, he’d spent more than six years as a prisoner of war in Vietnam until his release on March 4, 1973. He wanted information about an aircraft that flew him out of Hanoi. That aircraft — also a C-141 — had been his liberation, a resurrection of sorts. He’d heard Harlow could help him.

Harlow excused himself, and returned a minute later carrying an open binder. He turned it so Blevins could read the page. It was a passenger manifest for a flight from Gia Lam Airport in Hanoi to Clark Air Base, Philippines — March 4, 1973. The aircraft was a C-141 bearing tail No. 660177.

This aircraft.

The eyes of both men moistened. “Welcome home,” Harlow whispered. “This was your aircraft.”

Twenty-six years before it sat on the Randolph flight line, aircraft No. 660177 was one of 16 Air Force C-141s that carried American POWs home during Operation Homecoming. According to Harlow, just 11 of those aircraft still fly. Four of them, including 660177, are assigned to Air Force Reserve Command’s 445th Airlift Wing at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio.

But this aircraft, nicknamed “One-Seven-Seven,” has even greater significance to POWs. It flew the first Homecoming mission, carrying 40 men out of Hanoi on Feb. 12, 1973. Today, it’s often called the “Hanoi Taxi” and travels the world not only as an operational airlifter, but as a monument to brave men and their families.

“Although this was the first aircraft out of Hanoi, it represents all of the Homecoming freedom flights,” Harlow said. “It also represents the POWs who didn’t get a chance to come home and the families who didn’t see their husbands or fathers come down that ramp.”

Harlow, an air reserve technician, is the senior adviser for an ongoing POW “mission” that started four years ago when the 445th took possession of the aircraft. Its new crew chief, Tech. Sgt. Dave Dillon, noticed a worn blue label stuck to the engineers’ panel. Just a couple inches long, it bore two words: HANOI TAXI.

“We started asking questions and collecting information,” Harlow said. “It just kind of steamrolled from there.”

It steamrolled through the drive of Dillon, Harlow, Tech. Sgt. Jeff Wittman and a handful of other reservists in the 445th. They’ve volunteered time and money to turn One-Seven-Seven into a POW museum. The aircraft’s nose art is the shield of the 4th Allied POW Wing, the organization of Vietnam POWs. Inside, a plaque commemorates the first Homecoming flight on Feb. 12, 1973, and the walls are lined with photos documenting the POWs’ captivity, release and homecomings. Visitors can leave the aircraft with a fistful of literature on POW issues.

“The unit supports us, but many times we use our own money to obtain specific items for the display,” Harlow said. “And it’s not work to us. It’s a labor of love.”

The aircraft’s crew has become passionate in their admiration for the strength and bravery of the POWs. Their stop at Randolph was part of a small POW reunion (see “Freedom Flight” in September’s Airman), and Senior Master Sgt. Gary Fernandez, a flight engineer, collected autographs of former POWs for his young children. “Why do people want autographs of celebrities?” he asked. “These men are the real heroes. They have something to teach us, something we can look up to.”

Today, the aircraft is on the A-list of air show invitations, but frequently has to turn away the invites because it still flies real-world missions, including airlift operations earlier this year to Kosovo. “The only reason we can put the aircraft on display is if it’s not committed to a mission,” Harlow said.

Now 43, Harlow was a young, active duty airman during Operation Homecoming and remembers following it in the news. He’s become the aircraft’s senior advisor because he’s a walking warehouse of POW knowledge. “It’s a subject I’ve always been interested in,” he said. “I get the information wherever I can. I research and read everything I can get my hands on.”

He shares that lore with anyone who wants it. He gets several queries via mail each month, and left a 1998 airshow in Oshkosh, Wis., with 114 requests for information. “It took about three months, but every one of them has been answered,” he said.

Harlow’s knowledge includes detailed facets of those earlier, historic missions flown by One-Seven-Seven and other C-141s, back when the aircraft were painted white, with the bright red cross signifying a medical plane.

“The flight nurses basically bought the base exchange at Clark Air Base out of perfume, and sprayed down the entire interior of each airplane — all the bulkheads, from head to tail,” he said. “The POWs have told us that as they came around to the ramp at the back of the airplane, they could smell it. And to them, it smelled like America.”

Many POWs were captured before the C-141 entered service, so they’d never seen the new airlifter until they boarded one for a flight to freedom. “They tell us the aircraft represented America,” Harlow said. “It was the cleanest, most beautiful thing they had seen in a lot of years.”

Lt. Col. Norlan Daughtrey can’t say if his plane was clean. As one of the longest-held POWs, he was on that first flight out of Hanoi, Feb. 12, 1973, aboard One-Seven-Seven. “I never saw that aircraft because when I got on it, I was crying so hard,” he said. “And they were tears of joy.”

Lt. Col. John Yuill was one of the last POWs out of Hanoi in 1973. A B-52 pilot, he was shot down and captured during Operation Linebacker II, the December 1972 bombing campaign that is credited with winning the POWs’ release. More than 26 years later, he stood on the ramp of the Hanoi Taxi at Randolph, looking back into the cargo bay lined with photos of his fellow POWs. It was like looking through a time tunnel.

“You know, I’ve had only two rides in a C-141 in my life,” he recalled. “One was from Hanoi to Clark Air Base. The other was from Clark to Sheppard Air Force Base, Texas. So anytime I see a C-141, that’s what I think of.”

Harlow said his unit tries to make the aircraft available for any POW who wishes to visit. Such visits can be very emotional, or very solemn. He recalled one former POW who stared at a single photograph for nearly 40 minutes. “It’s a closure of sorts,” Harlow said. “When he was ready to move on, he moved on.”

To Lt. Col. John Blevins, that Friday afternoon at Randolph was more than a closure. He stood in the bay of the plane that carried him to freedom, struggling to find words. “It hits you in the gut,” he said haltingly. “It’s unbelievable.”

He called it a sort of homecoming.

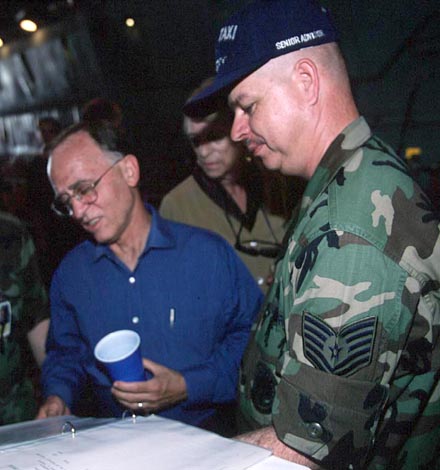

Tech. Sgt. Henry Harlow shows retired Lt. Col. John Blevins the manifest for Blevins’ 1973 freedom flight aboard the Hanoi Taxi. When he returned to the aircraft 26 years later, he had come full circle.

| If you want information about the Hanoi Taxi or any Vietnam POW,

Tech. Sgt. Henry Harlow will help you find the answer. Write him

at: PO Box 728 Fairborn, Ohio 45324-0728 |

Last Updated: 14/Aug/2004 10:03