StarLifter

The C-141, Lockheed's High Speed Flying Truck

by Harold H. Martin

Hospital in the Sky

YOKOTA AIR BASE in Japan, Clark in the Philippines, and Kadena in Okinawa are three outposts of America in the islands of the Far Pacific. At each the mood and pattern of daily living are purely stateside, touched but lightly and in no way changed by the life style of the people around them. The Base Exchange may carry the native handicrafts at prices low enough to keep the downtown merchants honest, a boon to transient flight crews who are passing through. A family may go by bus or car on a sightseeing tour to historic spots and noted shrines. Local nursemaids, cooks and houseboys, gate guards, and the workers who load the planes come and go, bringing in their manner and speech some faint flavor of the teeming life that swarms beyond the gates. But this is all.

At Yokota, for example, which lies in the heart of Honshu, base personnel who bring their families with them may live in western-style houses with lawns and gardens on quiet streets that differ in no obvious way from any small-town street in the United States. Their kids go to schools where the curriculum is the same as that at home. They play Little League baseball, join a Boy Scout troop, and learn lifesaving techniques as taught by the YMCA. Fathers play golf, and meet once a week with their stateside civic clubs. Mothers busy themselves with bridge, garden clubs, reading clubs, and the PTA. As at any base at home, the social life revolves around the Saturday night dances at the clubs, and idle chatter beneath bright umbrellas around the swimming pools on balmy days. Only a few decorative touches here and there impart a foreign flavor, a sense of the new and

strange, to a base that otherwise might be Kelley, Travis, or McGuire. There is a marvelous mural at the club at Kadena, for example, of marching horsemen and spearmen carved in dark wood, and a beautiful exhibit of brain and lace and staghorn coral in the Snack Bar. Hill Hacienda, at Clark, has an atmosphere all its own when the barbecue is cooking under the open sky. At Yokota, a little circular garden with its flowers and ancient twisted pine in front of the billeting office is a landscaped touch of old Japan. Walk a few steps down a narrow path, however, and a low door opens on a scene that is purely stateside. The Yokota Stag Bar, the most popular spot on MAC's Far Eastern itinerary, has the look and feeling of a workingman's all-night restaurant and saloon. Over the horseshoe bar a hand-lettered sign pays obscene disrespect to Communism. In one corner is a closed-circuit TV on which officers are paged, and which on occasion, for want of a better message, may carry the legend "Captain So-and-so is a fink." Weary and rump-numb in their baggy flying suits, MAC's dehydrated pilots make their way to this oasis even before they seek out their billets, take a bath, and turn over the laundry to the Mama-san. Lips cracked, throats parched, dry skin itching after a nine-hour flight in a pressurized plane that squeezes all but 2 percent of the moisture out of the air, they restore the body fluids with beer that costs only a dime a glass at a Happy Hour that starts at 5 A.M. Other specialties of the house are Yok soup, falsely alleged to be made by boiling a beast of burden which lives on the slopes of Mount Fuji. There is also a robust dish of steak and eggs. Available around the clock, this hearty fare breaks the gastronomic monotony of the average snack bar's leathery pizzas, greasy hamburgers, and the blandly tasteless TV dinners the loadmasters serve in flight.

However doggedly the Pacific bases may strive to wrap themselves in the cozy amenities of home, and to provide them for their visitors (at Kadena, for example, MAC crewmen may rent bicycles and Polaroid cameras for sightseeing), nobody in these quiet American enclaves can forget his mission here. Just a few hours' flight over the China Sea is the smoke and flame, the noise and dust and mud and weariness, the pain and the blood and the dying of what has been a full-scale war. The passengers who pass through are bound for that war, and the StarLifters that leave with their heavy cargoes may be making their next landfall in range of enemy mortars.

Particularly is the pressure felt at Yokota, hub of the great Pacific airlift wheel. Planes from both coasts funnel through here, bringing men, and war materiel of the highest priority. They carry dangerous cargoes-acids, gases, solids, marked with a green label for special handling, and tagged with colored tags that denote explosives, inflammables, corrosives, or radioactive or magnetic items. They carry whole blood packed in ice, plasma and biologicals, rattraps, flea powder, and food and drink. They bring back gun barrels, aircraft engines, propellers, helicopter blades, vehicles and electrical devices so badly broken or worn they must be sent back for repair to the Air Force's great logistics facilities at Kelley and Warner Robins.

They carry into the war zone planeloads of long, green plastic boxes, and they bring them back containing the bodies of the dead. Loadmasters are trained to handle them gently and reverently. They are always loaded on the airplane first, placed far forward, so that in an emergency, if the plane has to lighten its load, they would be the last cargo to be jettisoned. The head must always face forward, and they may never be stacked more than three high, and the bodies of men and women may not be stacked together. A story is told in MAC of a young Marine called home on an unexplained emergency. Near him as he took his seat in the plane was a green box. Idly he leaned forward, glanced at the tag, and learned why he was needed at home. The body in the box was that of his younger brother.

The planes from Vietnam also bring out the wounded-more than 10,000 of them a month, on the average, in 1969, down to 2000 a month by the end of 1971. Between 1966 and late 1971, 86,000 battle casualties had flown home, and these mercy missions lie at the heart of the MAC crewman's pride in himself, in the Air Force, in the plane he flies. It proves to him that he is not just an aerial truckdriver. Like the doctors and the nurses and the medics in the field, he, old Joe MacBlow-pilot, engineer, navigator, loadmaster-is doing his part to save men's lives.

One hundred years ago, in the Franco-Prussian War, the French first used airlift for removing wounded from the field of battle. During the Siege of Paris, 160 persons were transported by balloon from the city to the safety of hospitals outside. Almost from the beginning of flight the value of the airplane as an ambulance has been recognized. As early as 1910, seven years after the Wright brothers' flights, two naval officers at Fort Barrancas built and flew an ambulance plane. The War Department showed no interest. In 1918, a converted Curtis Jenny carried the first litter patient in aviation history-too late to be of help to the thousands of wounded in World War I who were bounced painfully to the rear in bone-shattering automobile ambulances. In 1921, the Military Surgeon General almost burst into song in praise of the new air-ambulances that by then were working on the Mexican border. "No longer will the luckless recruit who has been bested in a contest with a Western bronco be jolted in a rough-riding automobile over cactus and mesquite," he wrote, "but borne on silvery wings, cushioned by a mile of air, he will be conveyed in the twinkling of an eye to the rest and comfort of a modern hospital."

In the fifty years that have elapsed between the Jenny and the StarLifter, the use of the silvery wings and the cushion of air has made tremendous progress. In World War II almost one and a half million patients were moved out of the combat zones, and between hospitals in the United States. In the Korean War, forty-six thousand wounded were airlifted from the Far East to the United States, on island-hopping flights that took three to four days, from Japan to the West Coast. With the StarLifter transporting eighty patients at 500 miles an hour, wounded from Vietnam can now be delivered to Travis in seventeen hours, and to Andrews and McGuire in less than twenty-four. A patient may now be picked up anywhere in the world and transported to hospitals anywhere in the United States in less than thirty-six hours. In Vietnam an air ambulance is available to a wounded man almost from the moment he is hit. Army rescue helicopters swoop in under fire to pick him up for transport back to a field hospital. There, as soon as his wounds have been cleaned and sewed up and his shock diminished by the transfusion of blood and plasma, he is loaded onto the StarLifter's little brother, the

C-130 Hercules, and carried to the medevac pickup stations at Da Nang, Cam Ranh Bay, or Tan Son Nhut. Every week when the war was at its crescendo forty-seven of the more than two hundred StarLifters that came out of the States as cargo ships left Vietnam as flying ambulances. The less seriously wounded went to military hospitals in Japan-eight of which are within a few miles of Yokota. Until recently, when their wounds were healed they returned from here to duty in Vietnam. Now, as the war winds down, all wounded men-the more and less seriously hurt alike-are held at small casualty staging facilities at Clark and Yokota until their wounds "stabilize" and they have built up the strength to make the long flight home. Within hours, they are at Travis, Scott, Edwards, or McGoiire, where they transfer to smaller planes, the DC-9 Nightingales, especially built as hospital ships, which transport them to any one of four hundred hospitals around the country. This swift transition from the battlefield to a hospital bed has helped to save thousands of lives. In World War II more than four men died out of every one hundred wounded. By the time of the Korean War the rate was cut in half. In Vietnam, the figure has been reduced to one death out of every one hundred battle casualties.

Before the de-escalation of the war in Vietnam, the big base at Yokota had become the focal point for air-ambulance operations in the Far East, and the surge and ebb of the battle were reflected in the figures of the 56th Air Evac Squadron there. Before the Tonkin Bay incident in 1964, some 300 patients a month were passing through the Casualty Staging Facility at Yokota. By March of 1969 the tide had crested at 20,074. Lower figures since reflect our efforts to reduce the scale of the fighting.

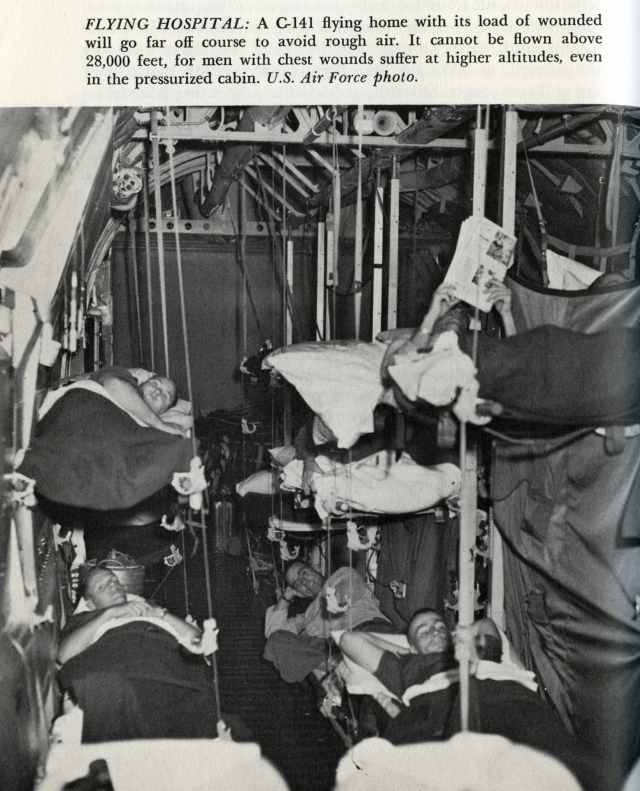

FLYING HOSPITAL:A C-141 flying home with its load of wounded will go far off course to avoid rough air. It cannot be flown above 28,000 feet, for men with chest wounds suffer at higher altitudes, even in the pressurized cabin. U.S. Air Force photo.

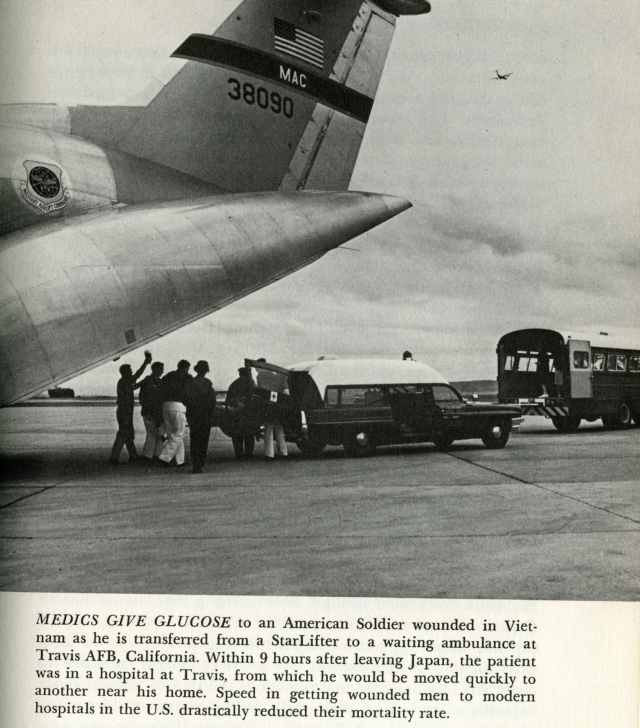

MEDICS GIVE GLUCOSE to an American Soldier wounded in Vietnam as he is transferred from a StarLifter to a waiting ambulance at Travis AFB, California. Within 9 hours after leaving Japan, the patient was in a hospital at Travis, from which he would be moved quickly to another near his home. Speed in getting wounded men to modern hospitals in the U.S. drastically reduced their mortality rate.

crews who will care for the wounded throughout their journey home. Gentle, compassionate, skilled in the healing art of making a hurt man comfortable, they range in age from leathery old lieutenant colonels with gray curls tucked neatly under their

Still the StarLifters keep busy. Late every afternoon, laden C-141's leave Yokota for Clark AFB in the Philippines, there to undergo a startling transformation from freight ship to flying hospital. Cargo and passengers are offloaded, and stanchions are set up on which litters may be hung. Seats for the walking wounded are installed, three abreast on either side of a center aisle. A comfort pallet is loaded on, a combination of kitchen stove, refrigerator, and latrine. It usually takes two hours to set up a StarLifter for an air-evac mission, but in an emergency,

the fast-moving 57th Support Squadron at Clark has done the job in forty-five minutes. Once ready, the ship, bearing its medical crew, takes off for Vietnam, arriving there before midnight and departing before dawn. Going in to bring back the wounded is a crisply efficient, highly dedicated medical team-two flight nurses and three medical technicians, one of a relay of such

>

>

>

>

jaunty flight caps to bright-eyed young nurse lieutenants just out of training, and med-techs who look like little boys beside the scarred old noncoms they serve. Their stamina matches their dedication. The crews who fly the airplane must fly no more than 125 hours in any consecutive thirty days, and no more than 330 hours in three months. The medical flight crews are under no such limitation. They fly when they are needed and many of them will fly 300 hours in a month. Calm people, not given to panic, they make light of the crises they encounter in the air.

"The worst thing that ever happened on one of my flights," a nurse major says, "was when the aircraft commander's flight suit zipper gave way, from throat to crotch. He had to leave the plane wrapped in a blanket." Another occupational hazard, a young nurse explained, was to walk downwind of a MAC crew after it had been out in the system about a week, moving too fast to get any laundry done. "Those green suits," she said, "can really get raunchy."

This levity is misleading. Emergencies do come up in flight, and the med crews are taught to handle them with quiet skill. In training they are subjected to a rapid decompression, which means they must grab a mask and portable oxygen bottle and immediately get as many as eighty patients breathing, each on his own oxygen supply. A great hazard of high-level flight is the sudden hemorrhaging of wounds when arteries rupture that have been hastily stitched at a field hospital. On one flight only the quick work of a medical crew under a flight nurse named Captain Margaret Frerich saved the life of a young Marine captain, whose leg wound began bleeding profusely on a med-evac flight from Elmendorf to Andrews. Finger pressure to check the bleeding and injections into the vein to prevent shock kept the young officer alive until the flight crew could put the plane down at Minot AFB in South Dakota. There doctors were waiting as the aircraft touched down.

While the maintenance crews are converting the plane to its air-evac use, the nurses and med-techs are checking their emergency kits-pumps to relieve tracheal congestion, catheters, syringes, hypodermics, bandages, and drugs. At the same time, the flight crew that is to take the plane in-country is checking in at operations for the special intelligence briefing that is given to all crews departing for Vietnam. This begins with the point the crews find most interesting-when the base to which they are going was last bombed or mortared, or came under sniper fire-and when it seems likely this might happen again. After giving them their radio codes, the briefing officer concentrates on the routes the planes must fly to avoid being hit by enemy small-arms fire, or by our own artillery firing close support for infantry troops in areas over which the plane will be making its approach. A plane coming into Da Nang's twin runways from the south, for example, is very likely to get a bullet in its tail if it makes too wide a turn. At Saigon, the main danger is from collision with friendly aircraft, the choppers and the C-130's that are always swarming there. At Cam Ranh Bay, the occasional mortar shell is always a hazard, as it is at Phu Cat and Bien Hoa. Crews are briefed on the location of the protective bunkers in relation to the ACP, and they are urged, when the siren blows, to head for these shelters in a hurry. From launch to impact, a 120-mm mortar shell spends about fifteen seconds in the air, and from warning siren to explosion the crew has about ten seconds to get underground. Obviously, Charley's mortarmen can pump in at least one round before the crews can take cover.

One is enough to start the action. Captain Bob Miller, a McChord pilot, recalls one of the rare mortar attacks on Da Nang. "It was very dark and we were moving into position on the ramp, and the guy with the lighted wands was signaling 'Come on, come on,' when all of a sudden he started crossing them very rapidly, the 'Stop!' signal, so we stopped. But then all we could see was one of the yellow wands lying on the ramp and the other one streaking off into the dark. About that time we heard the mortar explode. Not close to us, but any mortar explosion you can hear is close enough. So we piled out of the plane and sort of milled around in the dark for a couple of seconds, not knowing which way to run. Then we saw the yellow wand, far across the field, waving in a circle-the signal to 'assemble.' Well, we assembled all right. Six guys running flat out two hundred yards through pitch darkness hit the en-

trance to that bunker exactly together. We felt our haste was excusable. The plane we'd left in such a hurry was carrying 64,000 pounds of high explosives. Good thing it wasn't hit."

C-141's coming into the Vietnam fields start their let-down about one hundred miles out, level off at 6000 feet and come in fast on final approach. Ground controllers vector them away from artillery or small-arms fire, but there is always the possibility that a Communist controller, speaking perfect Air Force English, might come in on the local frequency and direct an unsuspecting crew into the path of hostile gunners. No Star-Lifter crew has fallen for this ruse yet, for there are electronic means of checking the ground stations' identity, and AC's are ordered to use them if there is the slightest suspicion the man on the ground may be a phony.

Whether the plane coming in is an air-evac ship or a cargo craft, there is no dawdling on the ground. While the AC and navigator go in to file their flight plan and get the weather briefing, the copilot keeps watch on the flight deck; the two engineers rove around on the outside, watching for possible sabotage; and on cargo flights, the loadmaster stays in the cabin to make sure the local workmen do not happily plant a booby trap amid the cargo pallets. Crews are warned to be especially watchful for any small items such as mechanical pencils or cigarette lighters left lying about after the loading crews have departed. Such innocent-looking devices have turned out to be firebombs or explosives.

Whether in Vietnam or at a way station such as Elmendorf or Hickam on the flyway home, the air-evac operation goes off with the smoothness of a practiced drill. The plane as it lands is surrounded by its helping machinery-the power generator to keep the pumps working in case the plane's own power unit should go bad. Heaters, air-conditioners if needed. Always a fire truck-"Any time you see a fire truck standing by an aircraft," a loadmaster says, "you know it's the Secretary of Defense, a four-star general, or an air-evac." In addition to the fire truck, a special crash-rescue team takes its post just aft and upwind of the plane in case a fire or explosion makes it necessary to offload the patients in a hurry. The aircraft may be refueled while

Hospital in the Skyji6i

patients are being loaded, but only after the fire chief or his senior deputy has satisfied himself that the plane is properly grounded and that no electrical circuits or switches will be turned on during the fueling process except cabin lights, the intercom, and the pumps and respirators that are serving the patients. At each base along the route the supporting agents are stationed in exactly the same spot, relative to the plane, from the ambulance buses that bring in the patients to the ramp-tramp's jeep, and the car bearing the Red Cross volunteers bringing soft drinks, cookies, and paperback books.

In the cold white glow from the lighting trucks, the action around an air-evac is an eerie sight at night. The walking patients come on first, in their blue hospital pajamas and-striped, flapping bathrobes, their scuffs slapping the asphalt. Moving doggedly under their own steam, they swing shakily on crutches, or stump along on walking casts. They are held rigidly in neck braces and body casts; their arms are in slings and their heads or hands are in bandages from which blood may still be oozing. Often it is a three-man job-two men to carry the litter, one man holding high the bottle from which the life-giving saline solution drips into the patient's arm during the few seconds required to move him from bus to plane.

Working with fierce concentration, the medical technicians unload the litter patients from the ambuses, swiftly but with great gentleness moving them into the plane, at an average speed of one litter every sixty seconds.

Aboard the plane, each man has already been assigned his special place. Before the plane arrives, the in-country NOD- the flight Nurse on Duty there-has made up a loading chart showing where each man's litter is to be placed, or where he is to be seated. The chart, along with the tag on his litter, gives the nature of his wound, any special attention he will need, and to what hospital he eventually will be delivered. These things are written in the medical shorthand of war and the Saturday night emergency ward at a stateside hospital. "GSW," gunshot wounds; "MFW," multiple fragment wounds (the mark of a booby trap); "FRX," a fracture. Occasionally something prosaically civilian shows up, such as acne, malaria, bursitis. or a

hernia. But mainly the wounds are tears in the flesh, still raw looking with the sutures sticking from them like stiff black hairs. Or burns, or broken bones. Not all war wounds are physical, of course. On every flight there are two or three men tagged as schizophrenic or psycho-physiological, whose minds have cracked under the strain of combat, or the use of drugs to alleviate the gray misery of homesickness. The middle seat in a row of three on one side of the plane is always saved for them, so they can be placed between two walking wounded who might, in emergency, be able to keep them under control. On the other side of the plane, the middle seats, if possible, are kept empty so that men with casts on their arms may be seated on either side. Among the litter patients, those needing close supervision and those in heavy casts are placed near the floor. Though litters can go up to the ceiling, they are rarely stacked more than three high. The blue skirts of the flight nurses are none too long, and it can cause a rise in the blood pressure of the men in the lower litters when the nurse has to climb up to administer medication to a man in the top row.

As coolly and deftly professional in their jobs as the flight crews are in theirs, the nurses and med-techs soon have their charges bedded down and strapped in, their pain eased, their raw nerves soothed with sedatives and kind words. The lights dim, the engines scream, the "silvery wings buoyed on their cushion of air" lift up. The StarLifter that came out bringing the tools of war goes home as a mercy ship.