StarLifter

The C-141, Lockheed's High Speed Flying Truck

by Harold H. Martin

More Mule Than Racehorse

IN WORLD WAR II, more than a thousand passenger planes, their seats ripped out, flew 400 million ton-miles hauling men, munitions, materiel, and medicines over The Hump from India into China. The Berlin Airlift was a year-long flow of transport aircraft that delivered 2,375,000 tons of food, fuel, and supplies into the divided city when the Russians cut off all surface transport. During three years of the Korean War, airlift moved 80,000 tons of supplies and 214,000 persons into the theater-a small thing when compared to the Berlin Lift, but a prodigious achievement when the long haul across the Pacific translates the figures into ton- and passenger-miles.

To the military men who participated in these latter exploits, two lessons stand out. One, airlift can perform tremendous feats. Two, the above tasks could have been accomplished more easily, safely, and cheaply if the Air Force had been able to employ bigger, faster, longer-range planes that had been especially designed for combat cargo lift.

The mood of Congress in the mid-fifties was not receptive to this thought. If the Air Force needed more airlift capability, the legislators felt, it should contract with the civilian airlines to do the job; a point of view that was echoed loudly in the press. Rather than appropriate money for military airlift, some House members suggested that the government should guarantee loans to the civilian airlines, so that they could build up their own cargo fleets.

As a result, MATS-the Military Air Transport Service-in the late fifties was less a military airlift agency than a civilian style airline dressed out in military trappings. According to General Howell M. Estes, Jr.-who later was to command MATS's successor, the far more combat-ready MAC, Military Airlift Command-"It didn't have any capability except to fly people, and boxes of limited size, from point A to point B. It couldn't drop anything by parachute, except from the C-124, which was a very bulky and ineffective aircraft for that purpose. The backbone of the cargo fleet was the C-118, the military version of the airlines' DC-6." The C-118 also evidently had its limitations, for commentators other than General Estes have described it as "a plane that, on a good day, can lift its own weight."

The Army was particularly unhappy about MATS's limitations. By the late fifties it was beginning to dawn on most military men that though the threat of annihilation might deter an aggressor from striking a first blow that could only be answered with a nuclear counterattack, the missiles in their hardened sites and the bombers on air alert did nothing to discourage adventurers who were nibbling away at the periphery of the free world. Nor were the overseas garrisons always in the right place when these adventures started.

What the Army needed, and what, it began to mutter, it was going to try to obtain for itself, was a fleet of planes capable of picking up an entire Army division with all its equipment and transporting it overseas in a matter of hours, ready to fight a conventional war.

Fortunately, just when the Air Force cause seemed darkest an articulate and dedicated supporter of the airlift idea came to the command of MATS. General William H. Tunner had run the airlift that flew The Hump in World War II. He had commanded the Berlin Lift, and the airlift services in the Korean War. He knew what MATS's obsolete and obsolescent planes could and could not do. So he told the Army, "O.K. Let's see what we can do for you with what we've got."

The project, called Big-Slam Puerto Pine, airlifted 21,000 Army troops and 10,000 tons of their gear to Puerto Rico, and brought them back in fourteen days. It proved what General Tunner knew it would prove-that MATS could do the job if pressed, but that it would strain its capabilities to the utmost.20/STARLIFTER

Tunner agreed with the Army commanders that what was needed was a plane that would only incidentally duplicate the civil airlift role. It would be a plane especially designed to haul heavy cargo over long ranges into short, rough airfields. The specifications stood out clearly in Tunner's mind. The plane, he said, should be a big plane that would carry heavy as well as bulky loads. It should be a high-wing plane, and you should be able to load and unload it straight in, from truck-bed height, either from the front or rear. This straight-in, truck-bed loading was important, for in the remote airfields to which such a plane would be carrying its combat cargoes, the high-lift trucks and the high forklifts the sideloading planes required would probably not be available.

He wanted a plane that could carry an "appreciable" load for 7000 miles-from California to the Orient, for example-and could carry a full load of 80,000 pounds for 2000 miles, or the distance from the West Coast to Hawaii. It should be a jet or a jet-prop plane, the General indicated, for a piston engine powerful enough to do the job would be too expensive to maintain. Above all, this plane had to be easy to maintain and economical to operate. It had to be as far as possible immune to Murphy's Law, the Air Force adage that says if there is any possible way to break something, or do something wrong, somebody will.

"In short/' said the General, "what we want is a workhorse plane, cheap to operate, of indifferent speed, relatively large and easy to load."

As the decade ended, Congress was finally in a mood to listen. It was clear to the legislators by now that the nuclear deterrent alone was not enough. The country needed trained and ready troops, backed up by the airlift capable of moving them anywhere in the world. Crises in Lebanon and the Congo served to intensify this conviction as the sixties began. Nothing was said about it publicly, but the growing threat of trouble in the streets of this country also made an air-mobile ready force more imperative than ever.

In March of 1960 Generals Lemnitzer and White, the Army and Air Force Chiefs of Staff, had come to an agreement on what airlift the Army needed and what the Air Force would attempt to provide. By July Congress, prodded by Representative E. Mendel Rivers and his airlift subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee, had provided the first funds-$310,-788,000. With this the Air Force was to make a start toward developing, building, testing, and procuring the planes it needed. With a nervous side-glance at the civil airlines, Congress specified that no planes so procured would be used by the military to carry passengers on regularly scheduled flights.Three years later, the big plane that rolled out of Lockheed's huge assembly hangar at Marietta, Georgia, into the August sun seemed strangely awkward. With its high tail and drooped wings and its black, buglike nose, it looked like some huge moth just struggled from the cocoon with its wings still wet.

But it would do the job.

To the engineers who had designed it, it was the plane that General Tunner had visualized-"more mule than racehorse, more truck than limousine."

To Tunner himself, it was something more. "This plane is more than an aircraft," he declared. "It is a symbol of a basic change in our national attitudes toward survival. It signifies the return of our military program from almost sole emphasis on all-out nuclear war to the more practical preparation for localizing conflicts which the free world constantly faces all over the globe."

Twilight was falling on the nuclear bomber. The sun was rising on a more versatile hero, the globe-girdling cargo plane.

The early sixties was a time of doldrums in the aircraft industry, and the announcement by the Air Force that it was ready to spend nearly a third of a billion dollars to procure a new cargo plane set off a frantic scramble among the giants of the trade. Everybody was after the contract.

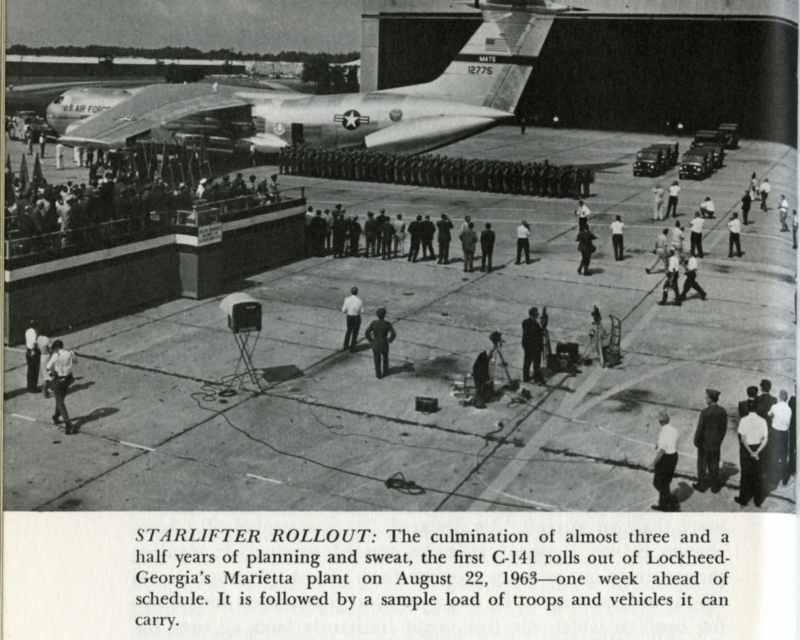

From the beginning, Lockheed was in a position of advantage. It knew how to build cargo planes. Since the mid-fifties the rugged prop-jet C-130 Hercules had been coming off Lockheed's assembly line at Marietta, Georgia, in a steady stream. A number of Congressmen and press commentators, concerned about military spending, had recommended that the plane the Air ForceSTARLIFTER ROLLOUT: The culmination of almost three and a half years of planning and sweat, the first C-141 rolls out of Lockheed-Georgia's Marietta plant on August 22, 1963-one week ahead of schedule. It is followed by a sample load of troops and vehicles it can carry.

bought should be an off-the-shelf item; one of the fast jets like the Douglas DC-8, or Boeing's 707, which were already in being. Or the Hercules itself, which was becoming famous for its cargo-lifting exploits from pole to pole and around the world. The Army itself gave support to the friends of the Herky-bird by announcing that it would be happy to have available a fleet of C-130s, as the plane best adapted to carrying out the Army mission.

Negative, said the Air Force, to both proposals. The DC-8 and the 707 were both fine airplanes for hauling passengers, or as cargo planes when operating into established terminals with long runways and specialized cargo-handling equipment. But they just did not have the rugged build and the short-field capability that a combat cargo-carrier would need. The Hercules was without doubt a great combat cargo-carrier, able to take the pounding of rough-field landings. But it was basically a tactical plane, designed for work within the combat zone. It didn't have the range or the speed or the weight-carrying capacity to function as the long-range strategic cargo plane the Air Force was looking for.

What the Air Force really wanted, and what it knew it could not ask for at the moment, was the optimum airlifter, a giant ship of global range that could carry a tremendously heavy load-a heavy hauler, like the C-5 Galaxy that is flying today. Such a plane, when teamed with a smaller carrier that was compatible in speed and range, could carry out with ease the Army's mission of moving an entire division, with all its gear and heavy weapons, across the ocean and into a battle stance within a matter of hours.

But the time wasn't right for requesting such a plane, and the Air Force did not push its luck. Even in a more amenable mood, Congress would not have found the money for so big and costly an aircraft. Whatever was built would have to be in the state of the art then existing. It would cost too much to push out to new frontiers, no matter how badly the Air Force needed the bigger plane. So, with the smaller bird in hand, plans for the big ship were put on the back of the stove, temporarily, and the operational requirement the Air Force finally came up with was for a far more modest carrier. It was a compromise plane. It could do part of the job, but not all of it, for it would not be able to haul some of the Army's biggest and heaviest equipment.

Out of these plans for a medium rather than a heavy cargo-carrier the StarLifter was born. It was far more plane than its stablemate, the Hercules, which for a time was its strongest rival. But it was far less a final answer to the military's airlift needs than was the huge Galaxy, which a few years later would shoulder it off the assembly line.

Before any kind of aircraft could be built, however, everybody even remotely connected with airlift had to put his ideas in the pot. The Army particularly, as the biggest potential customer outside the Air Force, had to be consulted. The FAA and the Air Transport Association expressed their views, for Congress,24ISTARLIFTER

fearful of criticism if they financed at taxpayers' expense a military cargo craft that might have no commercial use, had specifically required that the plane be certified by FAA as meeting all civil aviation requirements for safety and performance.

Nearly every agency of the Air Force itself had a finger in the pie. The Systems Command would shepherd the plane through production, procurement, and development testing. The Logistics Command would be responsible for maintenance and supply. The Training Command would get the first operational planes and in them it would train the crews that would fly the planes once they went to the operating squadrons. Even the Army Corps of Engineers got in the act, for it would have to build whatever special facilities, such as fueling ramps and hangars, that the new plane might require. The Department of Defense was particularly interested in its role as general overseer of all the services, for a new development in one arm of the military may affect the roles and missions of another. It also administered the Military Industrial Fund, through which users of the airplane would pay the Air Force for its services.

Most interested of all, of course, was MATS, the Military Air Transport Service, soon to be upped to the status of a full-fledged command. It was MATS, or later MAC, the Military Airlift Command, that would operate the plane-manning it, maintaining it, and flying it around the world. Any mistakes the other agencies made would be the operating command's headache later on.

Finally, after everybody had had his say, the Air Force came out with its formal "Statement of Work" and a "Request for a Proposal." These were presented simultaneously to Lockheed, Convair, Douglas, and Boeing. Boiled down, what the Air Force said was simply this: "Here's the job we want done. How would you do it, and what do you think it would cost?"

Al Cleveland, the tall, balding Lockheed Assistant Chief Engineer in charge of C-141 engineering, and Bob Gilson, the bronzed, bespectacled 141 Project Engineer, well remember that little billet-doux. It arrived at Lockheed's Marietta plant on December 21, four days before Christmas of 1960. An answer-the formal proposal-was wanted by the end of January. Nobody on Gilson's staff of five hundred draftsmen, designers, and aerodynamic engineers had a holiday that season, either at Christmas or New Year's. At Boeing, Convair, and Douglas the frantic effort was the same. Aerodynamics people, weights people, structures people all pored over slide rules and bent over drawing boards. The manufacturing people, tool planners, fabricators, assembly people, scheduling experts, even the finance and contracts specialists-all were busy over the Yule and deep into January.

Out of their labors came seven thick volumes describing the plane and its functions. It was all there: engineering configuration, production schedules, target price-the whole nine yards, as the airmen say-each man's talent and knowledge melding into that of every other specialist, just as on the drawing boards the wings, engine pods, nose cone, tail assembly, and landing gear all mated with the fuselage in one harmonious shape bespeaking speed and power.

When the January 31 deadline came, Lockheed was ready. No contract of this magnitude had been in competition for some time, and the company brought up its biggest guns when it made its oral presentation to the Air Force Evaluation Board at Wright Field at Dayton. Robert E. Gross, Chairman of the Board and chief executive officer of Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, presented Al Cleveland from Engineering, and W. A. Pul-ver, President of the Lockheed-Georgia Company, where the plane would be built if the contract was won. Cleveland made the technical engineering proposal for a plane he called the Super Hercules-fatigue resistant as the Air Force demanded, fail-safe, as civil air regulations required. Pulver explained how the program would be managed and funded. Standing by to back up Cleveland and Pulver were Courtney S. Gross, brother of Robert Gross and President of the parent corporation, and Dan Haughton, his Executive Vice-President. After the presentations, Robert Gross summed up. "Gentlemen," he told the Air Force experts, "Lockheed was founded to build transport airplanes and we have been building them for twenty-five years. • . . The fine response of our designers resulted in the airplane you have seen ... a worthy new member of a family of Lock-26/STARLIFTER

heed transports. I am convinced it is our best to date."

Pointing out "the vital realism of our cost and schedule proposals," Mr. Gross concluded: "No miracles are offered. We propose to do only that which we know we are capable of doing."

There was no more to be said or done, for each competing company was limited to one hour for its oral presentation. While their competitors went in to make their pitches, the Lockheed delegation went back to Georgia and California, to sweat and fret and wait and worry while the board, for forty days and nights, pondered, argued, and discussed. At Lockheed, Convair, Boeing, and Douglas, tension mounted to the breaking point. Finally on March 10 a rumor floated southward from Capitol Hill. Senator Richard B. Russell's office, it was said, had reason to believe that on March 13 President Kennedy would release to the press a statement that would be of deep interest to Lockheed.

This sounded like good news, and it was. The President's flat Boston accents rang like golden bells in Georgia as the White House announced that Lockheed, with Pratt & Whitney as co-contractor on the engines, had won the design competition with its plans for a "Super Hercules." It was to be a pioneering aircraft in the cargo field, the statement said, capable of carrying troops or heavy cargo at speeds of 440 to 500 knots, at ranges up to 5500 nautical miles.

At Lockheed's huge assembly hangar at Marietta, where the prop-jet Hercules and the JetStar were already being built under a roof that spread over forty-seven acres, men didn't wait to hear the details as the President's announcement was read over the intercom. A great shout went up, of mingled pride and happiness. This was a billion-dollar program the President had approved, and it meant work for all, for a long time to come. But it also meant that the Georgia company had proved its mettle. It had gone into the fiercely competitive field of aircraft design, had met the old giants head on, and for the first time had won a contract on its own.

Bob Gilson heard the news with a lifting of the heart. His first impulse was to gather up everybody in his shop and head for the nearest bar to celebrate. But there was too much work to do.

In his big office, where models of all the planes he ever worked on in a long career were on display, he reached for the telephone. He was calling the flesh-peddlers, the companies which provide engineering talent on a contract basis-highly skilled engineers and draftsmen who move from one new program to another as government contracts shift from company to company within the aircraft industry. Somewhere, and soon, Gilson had to find more than two thousand of them to beef up his own engineering cadre of five hundred as they began the infinitely detailed drawings that had to be in hand before subcontracts could be let.

In early April of 1961 a formal contract was signed for putting together the first five test-and-evaluation planes. It totaled |30,000,000, including $100,000 for spare parts and ground equipment. Estimated cost of the total program, over a period of five years, was $1.079 billion. By Air Force edict the name of the plane had been changed from Super Hercules to the more prosaic military designation of C-141. The name of StarLifter, chosen in a contest among Lockheed employees, was to come later.

All over the country phones began to ring in the offices of companies which served the aviation industry as Lockheed began to line up its subcontractors. The C-141 was to be a prodigious team effort, involving suppliers in nearly every state. Pratt & Whitney, co-contractor, was building the engines, each turning up 21,000 pounds of thrust. Avco was to build the wing-box beam; Twin Industries Corporation the wing's trailing edge; Bell Aero Systems the cargo floor plates, Bendix the main landing gear, Cleveland-Pneumatic the nose gear. The empennage, the high T-tail, was farmed out to General Dynamics, and the plane's environmental system-heating, cooling, and pressuriza-tion-went to AiResearch. The automatic flight control system was assigned to Eclipse-Pioneer. From Buffalo to Chattanooga to San Diego and points between, all these bits and pieces large and small would flow into Lockheed's assembly plant at Marietta, where they would be mated to the fuselage at tolerances measured in thousandths of an inch. Over the life of the contract, 61 percent of the plane by weight was built outside the Georgia plant, and 44 percent of the money Lockheed received was passed on to subcontractors.

"There's no little guy sitting off in a corner with a drawing board, sketching how he wants an airplane built," Bob Gilson explained. "The C-141 was a combined effort by thousands of specialists scattered all over the country. And the key to the whole thing was management. Fortunately, we had the best in the business. Chuck Wagner was a ramrod with a smile. He'd chew you out all week and then call you up on Sunday just to talk with you."

Charles S. Wagner, the Lockheed Vice-President given the job of managing the huge project in all its ramifications, was a self-taught, up-through-the-ranks airplane builder who knew every aspect of that vastly complicated job. Chubby, white-haired, deceptively mild mannered and soft-spoken, in his progress from oil-field roughneck to top executive he had somehow learned the knack of making men want to do their best for him.

By great good fortune, the Air Force chose as his military counterpart an officer with these same attributes. Colonel Max Hammond, the SPO (Systems Project Officer) for the Air Force, had been chief of the DOD Sources Selection Board. He knew what the Air Force wanted in the plane it was buying and he knew how to get it, with a minimum of friction between the Air Force and the manufacturer. Between the two of them, Wagner and Hammond got the C-141 project off the ground in a hurry. For six years it never slowed down, until February of 1968, when the 285th StarLifter rolled out and the assembly line closed down-to retool and refit for the plane the Air Force had had its heart set on all the time, the gigantic C-5 Galaxy.